Do BCAAs Really Build Muscle… or Just Build Hype?

What You NEED TO KNOW About Your Not So "Average" Amino Acids

Why Everyone’s Sipping Neon Liquid

Walk into almost any gym and you’ll see it:

Shakers full of neon liquid, people sipping between sets like it’s rocket fuel for muscle growth.

Ask what’s inside and you’ll usually get the same answer:

“Oh, it’s just BCAAs. They help with gains, recovery, you know.”

BCAAs have become that supplement, the one people buy first, understand last, and defend like a personality trait.

In this article, I want to do something very different from the usual “BCAAs are amazing!!” or “BCAAs are useless!!” echo-chamber takes.

We’re going to walk through:

What BCAAs actually are (on a chemical and physiological level)

What they can do for muscle, performance, and fatigue

Where the hype outruns the evidence

Potential downsides and gray areas nobody on TikTok mentions

How to use them intelligently or decide you don’t need them at all

And why, if you are going to take them, brand quality actually matters

No tribalism. No supplement worship. Just context, nuance, and mechanisms explained in human language.

What Are BCAAs, Really?

Let’s start at the beginning: BCAA stands for branched-chain amino acids, and there are three of them:

Leucine

Isoleucine

Valine

Think of amino acids as Lego bricks your body uses to build proteins: muscles, enzymes, hormones, immune proteins, basically a huge portion of what keeps you alive and functioning.

Of the 20 standard amino acids your body uses, nine are “essential,” meaning you cannot make them yourself. You have to get them from food or supplements.

Leucine, isoleucine, and valine belong to that essential club. But they’re a special subgroup because of their branched-chain structure, chemically, they have a little side branch in their carbon backbone. That structure:

Makes them more hydrophobic (they like to hang out in fatty or non-water environments)

Influences how they’re metabolized

And helps determine how they’re used in muscle tissue

Unlike many other amino acids that are predominantly processed in the liver, a large chunk of BCAA metabolism happens in skeletal muscle itself. That’s one reason they’re so interesting for athletes and lifters, they’re not just floating around waiting to be processed in the liver; they’re actively used by your muscles as both building blocks and energy-related substrates.

Leucine: The “Signal” for Muscle Building

If you want to understand BCAAs, you have to understand leucine.

Picture this:

Your muscles are a construction site.

Full protein (with all essential amino acids) is the pile of bricks.

Training is the building permit, telling your body: “We’re allowed to build here.”

Leucine is the foreman walking onto the site and yelling “Let’s start!”

In biochemical terms, leucine strongly activates a pathway called mTOR (mechanistic target of rapamycin). mTOR is a central growth regulator. When mTOR is activated in muscle cells, it cranks up muscle protein synthesis, the process of stitching individual amino acids together to build or repair muscle proteins.

So when you eat a protein-rich meal or take a supplement containing enough leucine, you’re essentially hitting that “go” button for muscle-building at the cellular level.

But here’s the twist that supplements rarely explain:

Leucine can shout “BUILD!” all day long, but if you don’t have enough other essential amino acids present, your body can’t actually complete the construction.

The signal (leucine → mTOR) and the raw materials (all essential amino acids) both matter. BCAAs give you a loud signal… but only 3 out of 9 essential bricks.

Keep that tension in mind, it’s a core reason why BCAAs are both biochemically interesting and easy to oversell

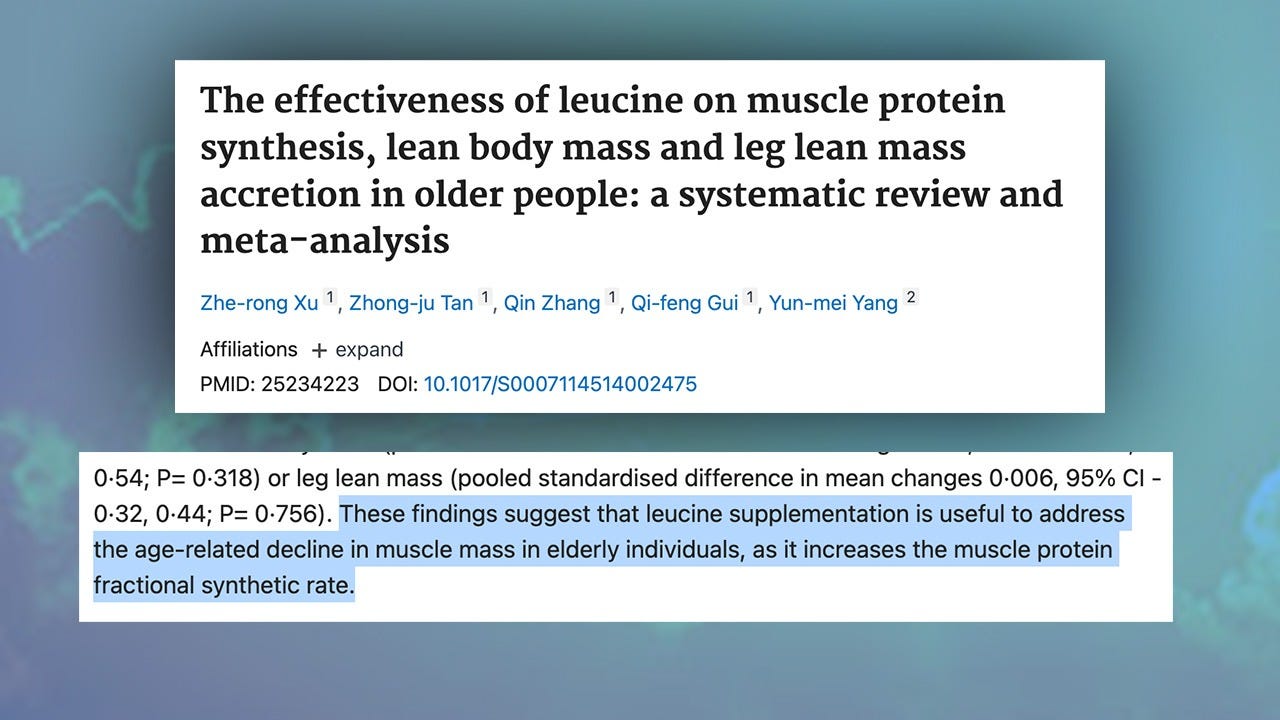

Side note: As we age our ability to build muscle and digest protein goes down, in many older populations sarcopenia can become a real downfall of vitality. Leucine has been shown to improve muscle protein synthesis in aging populations as well as help keep sarcopenia at bay alongside a well thought out lifestyle regimen.

Why Are BCAAs So Popular?

If you look at the science alone, you might think:

“Okay, so they’re three essential amino acids with some special roles. Why the giant tubs and fluorescent colors?”

A few reasons:

1. They’re easy to market

“Take this powder, grow more muscle, recover faster” is a much easier sell than:

“Lift progressively, sleep 7–9 hours, manage your stress, eat balanced meals, and worry about fine-tuning amino acid profiles once those basics are nailed.”

BCAAs are simple to explain at a surface level:

“These are the muscle-building amino acids.”

“This one (leucine) switches on muscle growth.”

“Sip this during your workout to avoid muscle breakdown.”

Some of those statements have a kernel of truth, but they’re usually presented without context.

2. They taste good and feel “hardcore”

Most BCAA products are flavored like candy. For a lot of people, it becomes:

A fun ritual

A flavored drink during training

A “fitness identity” symbol, shaker in hand, headphones on, BCAA label visible

Nothing inherently wrong with that, but it blurs the line between scientific utility and habit/identity.

3. There are genuine physiological reasons to study them

Because BCAAs:

Are essential

Are heavily used in skeletal muscle

And leucine is a key mTOR activator

Researchers have been interested in them for:

Muscle protein synthesis

Exercise performance

Recovery and soreness

Fatigue (especially central fatigue via effects on neurotransmitters like serotonin)

Even metabolic diseases and insulin sensitivity

So you have this combination of real biochemical importance + simple marketing story + gym culture adoption = BCAAs everywhere.

My Stance Going In (So You Know Where I’m Coming From)

I’m not “Team BCAA” or “Team BCAA is Trash.”

I’m team “What problem are you trying to solve?”

Over the rest of this article, we’re going to unpack:

When BCAAs can be a useful tool (like training fasted, very low protein diets, long/harsh sessions)

When they’re basically just expensive flavored water layered on top of an already sufficient diet

Some lesser-known downsides and metabolic questions that emerge at high intake or with certain conditions

How they compare to EAAs (essential amino acids) and simply eating more complete protein

And how all of this fits into a broader, health-first approach that also respects recovery methods like sleep, good nutrition, and for those who are more experimental — tools like red light therapy, hydrogen water, hyperbaric oxygen, and intermittent hypoxia (we’ll clearly label where evidence is solid vs emerging).

On a practical level, I want you to finish this series being able to answer, confidently:

Do I personally benefit from BCAAs, given my training, diet, and health status?

If yes, how should I dose and time them intelligently?

If no, what should I focus on instead?

Why Ingredient Quality (and Testing) Actually Matters

Here’s something that almost never shows up in flashy ads for BCAAs:

What’s not on the label may matter just as much as what is.

In most countries (including the U.S.), supplements live in this weird regulatory gray zone. They’re not regulated like prescription drugs, where you need clinical trials and pre-market approval. Instead, under laws like DSHEA, companies are mostly responsible for policing themselves:

They’re supposed to follow good manufacturing practices (GMP)

The FDA can step in after the fact if there are reports of harm or obvious violations

But there’s no automatic “FDA tested this exact tub of BCAAs and confirmed it’s pure” step before it hits your shelf

So the reality is:

Two BCAA products can look almost identical on the front

Same flavor, same ratio, same “sciencey” claims

But behind the scenes, the quality, testing, sourcing, and contamination risk can be completely different

And because BCAAs are something people might take every single day, that matters a lot more than most people realize.

The Heavy Metal Problem

Let’s talk about something unsexy but important: contaminants, especially heavy metals like lead, cadmium, arsenic, and mercury.

Where can they come from?

Soil and water where raw materials are grown or processed

Industrial processing equipment that sheds trace metals

Low-quality flavorings, colorants, and fillers sourced cheaply

Poor manufacturing practices and cross-contamination between product lines

This isn’t fear-mongering; it’s just chemistry and supply chains. If you’re concentrating ingredients into a powder and not rigorously testing, whatever contaminants are there can become more concentrated too.

Heavy metals are problematic because they tend to:

Bind to proteins and enzymes in ways that disrupt normal function

Interfere with mitochondria (your cellular “engines”), increasing oxidative stress

Compete with essential minerals like zinc, iron, and calcium

Accumulate over time in tissues like the brain, kidneys, liver, and bone

So imagine the irony:

You’re taking BCAAs to support muscle recovery and performance… but if the product is contaminated, you may be slowly adding more oxidative stress and metabolic burden in the background.

For someone who’s already training hard, stressing their system, and trying to optimize recovery, that’s the last thing you want.

Why “3rd-Party Tested” Isn’t Just a Buzzword

Because the supplement world is largely post-market regulated, the real safety net for consumers is:

Third-party testing

Transparent reporting

Brands that voluntarily hold themselves to higher standards

When I say “third-party testing,” I mean:

An independent lab (not owned by the brand) analyzes the product

They check that the label matches the contents (e.g., the actual grams of BCAAs)

They screen for contaminants like heavy metals, microbes, and sometimes banned substances

Ideally, they test batches regularly, not just once

This doesn’t mean a supplement magically becomes perfect or pharmaceutical-grade. But it dramatically reduces the chance that you’re getting:

Less of the active ingredient than you paid for

Or worse, extra things you definitely didn’t order, like heavy metals or other impurities

For something you take once a month, maybe you can be a bit relaxed. For something you might take every single workout, the bar needs to be higher.

Why I’m Picky About BCAAs

Because of all this, I look at BCAAs through two lenses:

Do you actually need them, given your training and protein intake?

If yes, is the product as “clean” and transparent as you’d want for something you’re ingesting regularly?

That second piece is why I’m fussy about which brand I’ll even consider, let alone partner with.

I gravitate toward brands that:

Use short, minimalist ingredient lists (no rainbow of dyes, unnecessary fillers, or chemical soup)

Are upfront about their sourcing and testing, including third-party lab checks

Have a clear, no-gimmick formula, BCAAs as BCAAs, not buried in a proprietary blend with a dozen other under-dosed ingredients

Fit with a broader, health-first philosophy, not just “bigger biceps at any cost”

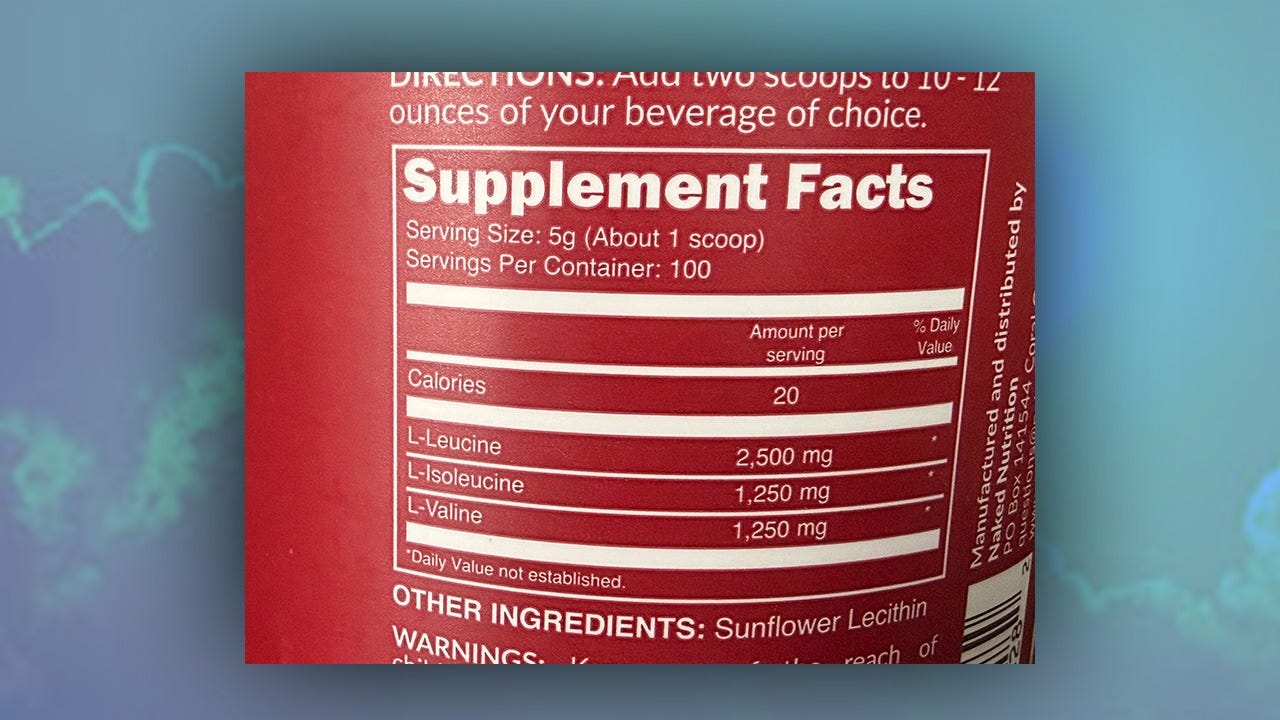

That’s the main reason I chose to partner with Naked Nutrition for BCAAs.

Their whole thing is a “nothing to hide” approach:

Focus on simple formulations rather than candy-store ingredient panels

A brand ethos that prioritizes cleaner, more transparent products

A vibe that aligns with the way I think about performance:

Not just “does this help my pump today?”

But “does this make sense for my body if I’m using it consistently over months and years?”

Try Naked Nutrtions Naked BCAA’s HERE

To be really clear:

You don’t need any specific brand to reach your goals. Plenty of people never touch BCAAs and still make fantastic progress just by hitting their protein, training smart, and recovering well.

But if you’re going to bring a supplement into your daily routine, especially a powdered product you’re mixing and drinking all the time, then ingredient quality, third-party testing, and a health-first formulation philosophy are absolutely not minor details.

They’re the difference between “smart, targeted support” and “expensive mystery powder that might be quietly working against you.”

From Shaker to Muscle: What Actually Happens When You Drink BCAAs

So you’ve got your shaker of BCAAs. You sip, now what?

What actually happens between that first sip… and your muscles doing anything meaningful with it?

Let’s walk through the journey.

From Mouth to Bloodstream (BCAAs Are “Fast Lane” Aminos)

Most people get their amino acids from whole protein:

Chicken, eggs, beef, lamb, fish , whey, etc.

Those are long chains of amino acids (polypeptides) that have to be broken down during digestion.

BCAA supplements are different: they’re typically free-form amino acids, not linked together in long chains. That gives them a kind of “express lane” through digestion.

In the gut

Your stomach and small intestine usually have to chop proteins into smaller peptides and then into individual amino acids.

With BCAA powders, that work is mostly already done, they’re pre-broken into single amino acids.

So absorption is:

Faster than a full meal

Less dependent on digestive capacity (no big protein unfolding/unraveling needed)

That’s one reason people like BCAAs around training, they hit the bloodstream relatively quickly without feeling like a heavy meal sitting in your gut.

Intestinal transporters

In the small intestine, BCAAs cross into your bloodstream using specific amino acid transporters embedded in the gut lining. You can think of these as specialized doors that recognize particular shapes of amino acids and let them pass.

Leucine, isoleucine, and valine use shared transport systems with other large neutral amino acids (LNAAs).

There’s a finite number of these transporters, which becomes important later when we talk about brain and fatigue.

Once absorbed, BCAAs enter the portal circulation (the blood going from your gut to your liver)… and this is where they start behaving differently from many other amino acids.

Why BCAAs Largely “Skip the Liver”

Most amino acids entering the portal vein get significantly processed in the liver. The liver:

Decides whether to use them for energy

Turn them into other compounds

Or release them into circulation in modified amounts

But BCAAs are the rebels of the amino acid world.

The liver lacks a key enzyme for them

To significantly break down BCAAs, you need an enzyme called branched-chain aminotransferase (BCAT).

The liver has very low activity of BCAT.

Skeletal muscle, heart, and some other tissues have much higher activity.

Result:

A large portion of the BCAAs you ingest bypass heavy liver metabolism and circulate relatively intact, ready to be taken up by muscle tissue and other peripheral tissues.

This is a big part of why BCAAs are so strongly associated with muscle: muscle is one of the primary sites that actually uses and metabolizes them.

Into the Muscle (BCAAs Cross the Border)

Once BCAAs are in systemic circulation (the “main bloodstream,” not just the liver’s portal system), they’re taken up by muscle cells through, again, specific transporters.

You can imagine muscle cells with gates that recognize BCAAs and pull them in when:

There’s enough BCAAs in the blood

There’s demand (e.g., exercise, energy stress, repair needs)

Inside the muscle cell, two main things happen:

BCAAs can be used as building blocks for new muscle proteins.

BCAAs can be partially broken down and used for energy (especially during prolonged or intense exercise).

But they also do something more subtle and powerful…

Leucine as a Cellular “Signal”

Leucine isn’t just a brick; it’s also a foreman that runs around the construction site screaming “Time to build!”

Biochemically, leucine activates a growth-regulating complex called mTORC1 (mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1).

What is mTORC1?

Think of mTORC1 as a central growth hub that integrates multiple signals:

Amino acid availability (especially leucine)

Energy status (via AMP/ATP, AMPK activity)

Mechanical load (resistance training, muscle tension)

Hormones and growth factors (insulin, IGF-1)

When enough of those signals line up, mTORC1 flips into “on” mode and increases:

Muscle protein synthesis

Ribosome activity (the machinery that builds proteins)

Various anabolic processes

How leucine fits in

Leucine activates mTORC1 through several mechanisms, but a simplified view:

Inside the cell, leucine interacts with proteins like Sestrin2 and Rag GTPases, which help “recruit” mTORC1 to the surface of a cellular structure called the lysosome.

Once mTORC1 is in the right place and enough leucine and other amino acids are present, the complex becomes active.

Active mTORC1 then phosphorylates downstream targets like S6 kinase (S6K) and 4E-BP1, which crank up the translation of mRNA → new proteins.

The leucine “threshold”

Your body doesn’t respond linearly to tiny amounts of leucine; there seems to be a threshold effect:

Below a certain dose → weak or no meaningful activation of muscle protein synthesis.

Hit the threshold → you get a noticeable spike in muscle-building activity.

Go way above the threshold → diminishing returns; you don’t keep doubling the effect forever.

This is partly why leucine-rich proteins (like whey) are powerful for muscle growth: they help reliably hit that leucine threshold within the context of a full amino acid profile.

BCAAs as Fuel (Not Just Building Blocks_

During exercise, especially prolonged or intense sessions, BCAAs can also be used as fuel.

The metabolic pathway (simplified)

Inside muscle cells:

Transamination

BCAAs are first acted on by BCAT (branched-chain aminotransferase).

This transfers their amino group to another molecule (usually α-ketoglutarate), creating branched-chain keto acids (BCKAs) and glutamate.

Let’s go deeper:

BCKAs are then processed by BCKDH (branched-chain α-keto acid dehydrogenase).

Eventually, they’re turned into intermediates that feed into the TCA cycle (aka Krebs cycle), the central hub of energy production.

For example:

Leucine → acetyl-CoA + acetoacetate (ketogenic)

Isoleucine → acetyl-CoA + succinyl-CoA (both ketogenic and glucogenic)

Valine → succinyl-CoA (glucogenic)

Energy production

These intermediates feed into the TCA cycle to generate ATP — your cell’s “energy currency.”

In other words:

When you’re training hard and burning through energy, your muscles can partially “burn” BCAAs to help meet the demand.

Is this the primary fuel? No, but BCAAs are part of that flexible metabolic toolkit.

BCAAs, the Brain, and Fatigue (Central Fatigue Hypothesis)

Now we move from muscle to brain, because BCAAs have another interesting role: they compete with other amino acids at the blood–brain barrier.

Remember those large neutral amino acids (LNAAs)? They share a transporter into the brain. This group includes:

BCAAs (leucine, isoleucine, valine)

Tryptophan (the precursor to serotonin)

Tyrosine, phenylalanine, etc.

They all use the same basic “brain gate” transporter.

The central fatigue idea

During prolonged exercise:

BCAA levels in the blood can drop as muscles take them up.

Free tryptophan in the blood may rise.

More tryptophan crosses into the brain relative to BCAAs.

Tryptophan → serotonin, which is involved in perception of fatigue, mood, and effort.

The central fatigue hypothesis suggests:

If you boost BCAA levels in the blood (like by drinking a BCAA supplement during exercise), you might reduce tryptophan’s relative access to the brain, slightly blunting serotonin’s fatigue-promoting effects.

That’s the theory behind BCAAs potentially:

Reducing perceived exertion

Improving mental stamina in long-duration exercise

The evidence is mixed (we’ll get into that in later pages), but mechanistically, that’s the story: competition at the brain’s amino acid gate.

So What Happens When You Sip BCAAs During a Workout?

Let’s put this all together in a real-world scenario:

You’re halfway through a workout, drinking a BCAA solution.

Fast absorption

Free-form BCAAs are quickly absorbed in the small intestine.

Circulation and muscle uptake

Because the liver doesn’t aggressively break them down, a significant amount reaches systemic circulation and then muscle tissue.

Inside the muscle

Leucine helps activate mTORC1, nudging your muscle toward a more anabolic (muscle-building) state, especially in the context of the mechanical tension from lifting.

Some BCAAs are used as fuel, contributing a bit to ATP production via the TCA cycle.

Systemic signals

A BCAA drink, especially if it contains some carbs, can trigger a small insulin response.

Insulin is itself anabolic and anti-catabolic (it helps reduce muscle protein breakdown)

Brain effects

Increased blood BCAAs may slightly change the ratio of BCAAs to tryptophan at the blood–brain barrier, potentially influencing fatigue perception.

Is all of this going to make or break your gains in a single session? No.

But mechanistically, these are the levers BCAAs are pulling:

Signaling (mTORC1)

Substrate (amino acid building blocks)

Fuel (TCA cycle intermediates)

Potential brain/central fatigue modulation

The big caveat, which we’ll keep returning to, is this:

If you don’t have enough of the other essential amino acids from your overall diet, you’re sending a “build” signal (leucine) to a half-stocked construction site.

That’s one of the main reasons BCAAs are both fascinating and not a crutch at the same time.

The Good: When BCAAs Actually Help

Now that we’ve walked through what BCAAs do in the body, let’s talk about when they can actually be useful, not just hype in a neon shaker.

BCAAs are not a magic muscle powder.

They’re a targeted tool that shines in specific contexts:

When you’re training fasted or under-fueled

When total protein is low or inconsistent

During long or brutal sessions

For some people, when soreness is out of control

Let’s go through those without getting lost in 50 sub-clauses.

Fasted Training If you roll into the gym:

Early morning

On an empty stomach

Or deep in a calorie deficit

…your body is walking a tightrope between performance and preserving muscle.

Mechanistically, here’s why BCAAs can help:

Leucine + mechanical tension from lifting = stronger mTORC1 signaling → promotes muscle protein synthesis.

Insulin bump: even without carbs, BCAAs can trigger a small insulin response, which helps reduce muscle protein breakdown.

As fuel, BCAAs can be partially oxidized to support ATP production when energy is tight.

So a BCAA drink before or during training is like a small “don’t eat my muscle” nudge:

It doesn’t replace a proper meal

But it can give your muscles enough signal + substrate to reduce the stress of training on an empty tank

If you’re dieting hard, lean, and training intensely, this is one of the more defensible use cases.

Low-Protein or Hard-to-Reliably-Protein Diets

If you’re consistently hitting ~1.6–2.2 g/kg of high-quality protein per day, you’re already giving your body plenty of full amino acid “building kits.”

But not everyone is there.

Common scenarios:

Plant-based eaters relying heavily on lower-protein foods

Busy professionals who regularly under-eat protein

People who “forget to eat” around training or have appetite issues

Travel, weird schedules, poor food access

In those cases, BCAAs are not as good as fixing the root problem (total protein intake), but they might be better than doing nothing.

Mechanistically:

They ensure at least leucine-rich pulses to help hit that mTORC1 “build” signal a few times a day.

They can modestly support muscle maintenance when your overall amino pool is suboptimal.

Think of it like this:

Ideal = full toolkit (all essential amino acids from real protein)

Reality for some = you barely have a toolkit

BCAAs = a small, fast-grab kit with just a hammer and a drill

You can’t build the whole house with that, but it’s still better than being completely empty-handed.

Endurance & Long Sessions: The Fatigue Angle

If your training looks like:

Long runs, rides, or hikes

90+ minute lifting sessions

Sports practices with repeated high-intensity bouts

Then you care not just about muscle, but fatigue management and mental sharpness.

Here’s where the central fatigue hypothesis comes back:

BCAAs and tryptophan share transport into the brain.

During long exercise, blood BCAA can drop, and free tryptophan can rise.

More tryptophan → more serotonin → higher perception of fatigue.

Drinking BCAAs during long efforts:

Raises blood BCAA levels

Changes the BCAA:tryptophan ratio

May slightly reduce how cooked you feel mentally

The data is mixed, not every study shows a clear performance boost, but enough suggests that some people feel:

Lower perceived exertion

Slightly better mental focus

Less “brain fog” at the end of long sessions

If you’re doing long endurance work or marathon-style gym days, this is another situation where BCAAs are at least biologically plausible, not just candy water.

Soreness & Recovery: DOMS Support (Especially for Newer or Deconditioned Lifters)

DOMS (delayed onset muscle soreness) is that wonderful “I can’t sit on the toilet” feeling 24–72 hours after a hard session.

Some research suggests BCAAs can:

Reduce perceived soreness

Improve functional recovery (e.g., strength returning quicker)

Especially in people who are:

New to lifting

Doing novel or very eccentric-heavy workouts

Under-eating protein in general

Mechanistically, this could come from:

Improved muscle protein turnover (more efficient repair)

Slightly reduced muscle damage markers

Better maintenance of amino acid availability during and after training

The Caveat: when someone already has high protein intake and solid nutrition, BCAAs don’t consistently add much here. But for beginners or people with shaky diets, they can be a noticeable “comfort and function” nudge.

“Lightweight” Intra-Workout Nutrition

A full protein shake mid-workout can feel:

Heavy

Sloshy

Not great if you’re doing anything high-intensity

BCAAs let you:

Sip something light that doesn’t feel like a meal

Still provide some amino acids and signaling

Combine easily with electrolytes and water for hydration

In a more naturopathic / health-first framework, you might also see people pairing BCAAs with:

Electrolytes for fluid balance

Possibly hydrogen-rich water (speculative but interesting for oxidative stress and recovery; evidence is still emerging, not settled)

Carbs, if performance is the main goal

Again, not essential, but for people who like sipping something during their session, BCAAs are one of the least “heavy” options.

So, Who Actually Stands to Benefit the Most?

If you check most of these boxes:

You often train fasted or in a calorie deficit

Your protein intake is inconsistent or on the low side

You do long or intense sessions

You’re struggling with excessive soreness as a newer lifter or returning after a break

…then BCAAs are more likely to give you real value, not just placebo.

If, on the other hand, you:

Eat a high-protein diet consistently

Train moderately and aren’t pushing intensity or duration

Already take a good protein shake around your sessions

…then BCAAs are probably closer to “flavored gym water” than a game-changing supplement.

The Bad (and a Little Ugly): Where BCAAs Fall Short

By now, BCAAs probably feel less like magic and more like what they are:

three useful tools in a much bigger toolbox.

Let’s talk about where they don’t live up to the marketing, and a few things people rarely mention.

BCAAs Are an Incomplete Building Kit

Remember:

BCAAs = 3 out of 9 essential amino acids.

Leucine can flip the mTORC1 “build” switch, but if the rest of the essential amino acids aren’t around, your body:

Increases muscle protein turnover

But doesn’t necessarily net out with more muscle gain

Think of it like this:

BCAAs can speed up construction activity on the job site,

but if the truck with the rest of the materials never arrives, workers mostly end up rearranging what’s already there.

Mechanistically:

Leucine → activates mTORC1 → upregulates protein synthesis machinery

But full protein synthesis requires all essential amino acids

If they aren’t available, your body starts breaking down other proteins to free them → not ideal

This is why many studies comparing BCAAs vs. full protein (like whey or EAAs) show:

BCAAs alone: modest or limited effect on net muscle protein synthesis

EAAs or high-leucine, complete protein: clearly better anabolic response

If you’re already eating enough complete protein, BCAAs very often don’t add anything meaningful on top.

The “More Leucine, More Muscle” Myth

Supplement labels love to brag:

“4:1:1”

“8:1:1”

“Mega-leucine!”

As if cranking leucine higher and higher is always better.

In reality:

There’s a leucine threshold for stimulating muscle protein synthesis

Once you hit it, adding more doesn’t linearly increase the effect

You still need the rest of the essential amino acids to actually build tissue

Also, hammering the leucine/mTORC1 pathway all day isn’t automatically better for health.

mTOR is a growth and anabolic pathway

Chronically high mTOR activation is being studied in relation to aging, cancer biology, and metabolic health

That doesn’t mean leucine is “bad,” but it does mean more isn’t always better in a 24/7 way

For muscle, the strategy is:

Pulse mTORC1 with training + feeding, not drown it in constant leucine without context.

Redundancy in High-Protein Diets

If your diet already looks like:

1.6–2.2 g/kg/day of high-quality protein

Regular meals with complete amino acid profiles

Possibly a whey or plant-blend shake around training

Then your system already has:

Plenty of leucine pulses

Plenty of essential amino acids

Regular mTORC1 activation in response to meals + training

In this scenario, adding 5–10 g BCAAs on top:

Rarely changes total muscle protein synthesis in a meaningful way

Often just gives you expensive flavored water plus a tiny bump in nitrogen

From a mechanism standpoint, you’re not fixing a bottleneck.

You’re just dumping more bricks onto a site that already has stacks of them.

For high-protein lifters, most of the “gains from BCAAs” are likely:

Placebo

Slightly tastier hydration

Or marginal at best

The Metabolic “Ugly”: When BCAAs Are Too High

This is more nuanced, but it’s worth mentioning.

Large observational studies have found:

Higher circulating BCAA levels are associated with

Insulin resistance

Higher risk of type 2 diabetes

Certain metabolic syndrome patterns

Important Note:

These are associations, not proof that BCAAs cause disease.

It’s very possible that:

Metabolic dysfunction impairs BCAA breakdown

So BCAA levels rise as a consequence, not a cause

Still, when you see:

Chronically elevated BCAAs

Impaired activity of BCKDH (the enzyme that helps break down BCAAs)

Accumulation of BCAA-derived intermediates

Over-activation of mTOR/S6K pathways that may interfere with insulin signaling

…you get a picture where constantly high BCAA exposure in an already insulin-resistant person might not be ideal.

Does that mean a moderate BCAA supplement will break a healthy person? No.

But if someone:

Is overweight

Has prediabetes/diabetes

Has known insulin resistance

…then hammering high-dose BCAAs all day “for gains” is not automatically benign. That’s a “talk to your practitioner” situation, not a DIY metabolism hack.

Additives, Sweeteners, and Gut Considerations

The other ugly part isn’t the BCAAs – it’s everything around them.

Many BCAA products are:

Heavily artificially sweetened

Packed with dyes, fillers, “mystery flavors,” or sugar alcohols

Created to taste like liquid candy

If you’re:

Drinking that every single day

And you care about gut health, microbiome balance, or long-term additive exposure

…it’s worth reading labels.

From a naturopathic perspective:

The amino acids may be fine

But the delivery system (sweetener load, colorants, etc.) may not be something you want as a daily staple

This is one reason a “cleaner” or more minimalist product actually matters (like that of Naked Nutritions Naked BCAA’s), not because it makes BCAAs more magical, but because it reduces unnecessary junk around an otherwise simple molecule.

Not for Everyone: Medical Red Flags

Finally, there are specific cases where BCAA use needs medical supervision or avoidance:

Maple syrup urine disease (MSUD): a genetic disorder of BCAA metabolism — BCAA buildup becomes toxic.

Significant liver disease: amino acid handling is altered.

Some neurological conditions and inborn errors of metabolism.

If someone is in any of these categories, BCAAs are not a casual “gym supplement.”

They’re something that belongs strictly in the “ask your specialist first” bucket.

So… Should You Actually Take BCAAs? (Conclusion)

Let’s zoom out.

You now know:

What BCAAs are

How they move from gut → blood → muscle → mitochondria → brain

Where they help

Where they’re mostly hype

Where they might even be a poor fit

Here’s the distilled version.

Ask Yourself 5 Questions

Am I hitting my protein target most days?

Roughly 1.6–2.2 g/kg/day if you’re actively training and want muscle.

If no, fix this first. Whole protein beats BCAAs almost every time.

Do I often train fasted, in a deficit, or under-fueled?

If yes, BCAAs around training might help support muscle maintenance and reduce breakdown.

Are my sessions long or brutal enough that fatigue is a real limiter?

Endurance work, 90+ minute lifts, sports practices: BCAAs may help a bit with perceived fatigue and recovery, especially if your nutrition isn’t locked in.

Am I new to training or coming back after time off and wrecked with DOMS?

BCAAs might ease soreness and support functional recovery, particularly if your protein intake is shaky.

Do I have any metabolic, liver, or rare genetic issues?

If yes, BCAAs go from “casual supplement” → “only with professional guidance.”

If you’re well-fed with protein, not fasted, and training moderately, BCAAs are probably not a needle mover.

The Real Hierarchy (No One on the Label Tells You This)

If your goal is muscle, performance, or recovery, the order of operations is:

Training stimulus

Progressive overload, good programming, actual effort.

Total daily protein

Enough grams per day, from mostly complete sources.

Overall diet & recovery

Calories, carbs around training, micronutrients, sleep, stress, hydration.

More targeted tools

Protein timing, maybe EAAs if eating is tough.

Naturopathic / adjuncts like red light therapy, hydrogen water, hyperbaric, intermittent hypoxia, interesting, emerging, but still add-ons, not fundamentals.

Fine-tuning with BCAAs (if they solve a real problem)

Fasted training support

Low-protein days

Long sessions + mental fatigue

Beginners getting crushed by soreness

BCAAs belong firmly in category 5, not category 1.

How to Use Them If You Decide They Make Sense

If, after all this, BCAAs still have a place for you:

Dose: ~5–10 g around training is typical; more is rarely better.

Timing:

Pre- or intra-workout if fasted or under-fueled

Optional on very low-protein days between meals

Pairing:

With water + electrolytes for hydration

Carbs if you’re chasing performance, not just muscle preservation

Product choice:

Look for clear labeling, simple ingredient lists, minimal unnecessary additives.

Choose a brand that aligns with a “nothing to hide” philosophy rather than a cartoon-candy circus.

My Final Thoughts

BCAAs are neither saints nor villains.

They’re three essential amino acids with:

Real biochemical roles

Real use cases

Real limitations

And real potential to be overused, misused, or just oversold

If you see them as a small, situational tool inside a much bigger health and performance strategy, not the foundation, you’re already using them more intelligently than 90% of people with neon shakers.

And honestly? Even if you never take another gram of BCAAs, but you walk away understanding how muscle actually grows, how amino acids really work, and where to focus your effort…

Sincerely your friendly neighborhood health nerd,

Ryan

REFERENCES:

Core BCAA / Muscle Mechanism & Efficacy

Wolfe RR. Branched-chain amino acids and muscle protein synthesis in humans: myth or reality?

Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. 2017;14:30.Kimball SR, Jefferson LS. Signaling pathways and molecular mechanisms through which branched-chain amino acids mediate translational control of protein synthesis.

Journal of Nutrition. 2006;136(1 Suppl):227S–231S.Churchward-Venne TA, Rerecich T, Mitchell CJ, et al. Leucine supplementation of a low-protein mixed macronutrient beverage enhances myofibrillar protein synthesis in young men: a double-blind, randomized trial.

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2014;99(2):276–286.Tipton KD, Ferrando AA, Phillips SM, Doyle D Jr, Wolfe RR. Postexercise net protein synthesis in human muscle from orally administered amino acids.

American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1999;276(4):E628–E634.

Performance, Fatigue & DOMS

Jackman SR, Witard OC, Jeukendrup AE, Tipton KD. Branched-chain amino acid ingestion can ameliorate soreness from eccentric exercise.

Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2010;42(5):962–970.Blomstrand E. A role for branched-chain amino acids in reducing central fatigue.

Journal of Nutrition. 2006;136(2):544S–547S.

Metabolic Health & BCAAs

Newgard CB, An J, Bain JR, et al. A branched-chain amino acid-related metabolic signature that differentiates obese and lean humans and contributes to insulin resistance.

Cell Metabolism. 2009;9(4):311–326.

Protein Intake, Hypertrophy & Practical Context

Morton RW, Murphy KT, McKellar SR, et al. A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression of the effect of protein supplementation on resistance training–induced gains in muscle mass and strength in healthy adults.

British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2018;52(6):376–384.Phillips SM, Van Loon LJC. Dietary protein for athletes: from requirements to optimum adaptation.

Journal of Sports Sciences. 2011;29(S1):S29–S38.

Big-Picture mTOR / Growth Signaling

Saxton RA, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth, metabolism, and disease.

Cell. 2017;168(6):960–976.